As a gardener, I’m always on the lookout for more plants. Colorful plants. Boisterous plants. Plants that make you go WOW! But when it comes to hydrangeas, I’m partial to the “simpler is better” philosophy.

That’s why my favorite types of hydrangea are the climbing ones (Hydrangea anomala subsp. petiolaris). I was lucky enough to inherit two mature vines from the former owners of my house, and I’ve been smitten ever since.

I’ve already decided that if I ever relocate to a different place, the first thing I’ll be doing after unloading the moving truck is planting some climbing hydrangeas. And I’ve already taken cuttings from my hydrangeas, just in case.

I like climbing hydrangea varieties because they are very low maintenance. In fact, the only maintenance you’ll need to do is some deadheading and light pruning in late winter or early spring. Add to that the heart-shaped deep green foliage and the lacey white flowers and you have the perfect vine for privacy and aesthetics.

3 Reasons why I don’t prune my climbing hydrangeas in the fall.

Our regular readers will remember that I’ve included this hydrangea on the list of plants you shouldn’t prune in the fall. I’ve already explained that’s because the new buds will come out on the old wood. And by pruning the plant too early, when the buds are barely visible, you risk removing the following year’s flowers.

But there are other reasons why I leave the dry flowers on the vine until February. First, I’m very much into the dry flower aesthetic in the winter garden. I like there to be something – anything – to capture my attention as I scan the garden in the winter from the coziness of my living room. The dry flowers have volume and move gracefully in the wind, so they add a lovely texture to the garden in an otherwise dead season.

Secondly, the full vine, even without the leaves, acts as a barrier. The climbing hydrangea in my backyard is growing through the fence that I share with my neighbors, weaving in and out from our side to theirs. When it’s fully leafed out in the summer, this vine makes for excellent natural soundproofing between the two yards. And it retains some of the same properties in the winter, especially if I leave the dry flowers on.

Similarly, the vine that grows up a trellis along the front of my house acts as a windbreak and mitigates some of the exposure of the building. So the fuller, the better, especially in the winter.

How to deadhead and prune your climbing hydrangea in spring.

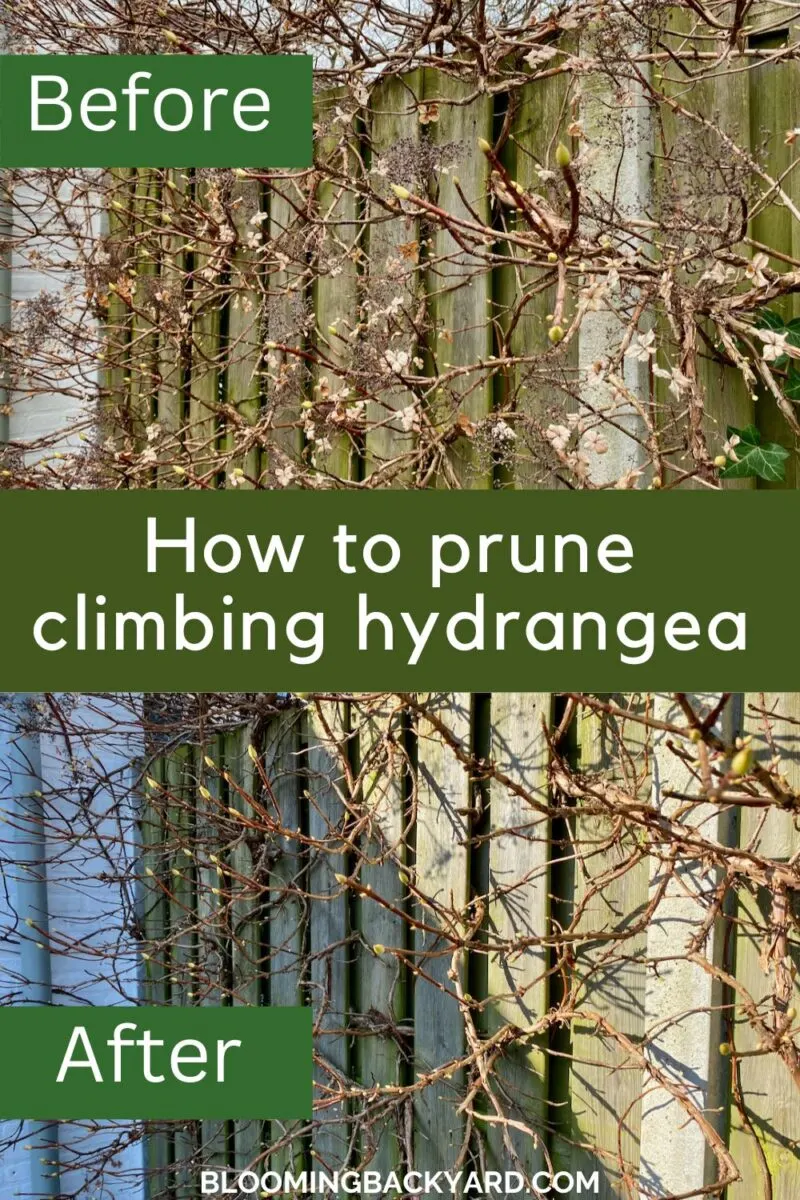

With winter on its way out in late February, it’s time to clean up my climbing hydrangeas. The new buds are already swelling up and showing signs that they’ll be opening up soon; if my calculations are correct, that will happen in less than three weeks. So it’s out with the old and in with the new today.

But before we merrily chop away, please keep in mind this one detail: climbing hydrangeas are slow growers that can’t handle hard pruning. Excessive pruning will damage the plant, and it might take years for it to recover. We’ll only be cutting off dry flowerheads, dead branches and errant growth. That’s it!

1. Start by pruning off the dry flowers.

First, start by deadheading the dry blooms as close as possible to a main vine or a main node. Because this hydrangea is really tall (and I’m not), I find it easier to start from the middle and work my way toward the margins. Opening it up from eye level allows me to see what needs to be pruned both above and below my direct line of sight.

I follow the petiole of the dead flowers all the way down to where it meets the vine. Some of the flower heads are already so dry that they’re snapping, but none have fallen.

You’ll notice that most of the heads feel dry and brittle to the touch, a clear sign that they’re dead. And when you cut into them, the scar left behind is brown. But every now and then, you’ll be cutting into wood that’s still green. That’s ok, as long as most of what you’re removing is already dried out.

However, you may also notice that there are new buds on some of the stems that you’re cutting off. This means the stems are still alive and will produce leaves and even flowers this spring.

I prefer to just cut these stems back to the buds, rather than cut them all the way down to a main branch. But if you think the foliage is thick enough as it is, go ahead and cut off these secondary buds too.

I estimate I found new growth on old deadheads only about ten percent of the time. So it’s a good problem to have, albeit not a common one.

2. Prune to encourage side branching, if needed.

When the vine is in its full glory in the summer, I keep track of where the gaps in the foliage are. (I just tie a bit of ribbon or a piece of twine close to the area.) That’s where I’ll prune back one of the larger branches to a junction in order to encourage side branching.

But just like I mentioned before, climbing hydrangeas are slow to grow back if you prune them too heavily. So I make sure I don’t cut back too much in a single year. Even when it comes to pruning for bushiness, I prefer to stagger that over several seasons, cutting back a branch or two in spring (before flowering) and in late summer (after flowering).

3. Cut back dead branches, if any.

This vine is anchored to the fence pretty well, so it usually doesn’t get too shaken by strong wind gusts. Some years, there are no dead or damaged branches at all.

But this year, when I was deadheading this hydrangea, I noticed there is a pretty good chunk of it without any new growth. It also felt light and hollow when I pulled at it. I suspect this branch had been cut off by my neighbor on the other side of the fence. No harm done! I cut it close to the fence, then pulled out what was left of it.

Climbing hydrangea is probably the easiest vine to cut back. For the most part, you’ll just need to follow the plant and let it guide your pruning. What do you think of this before and after?